Marine Science News 2020

Octogenarian snapper found in WA becomes oldest tropical reef fish by two decades

An 81-year-old midnight snapper caught off the coast of Western Australia has taken the title of the oldest tropical reef fish recorded anywhere in the world. The octogenarian fish was found at the Rowley Shoals—about 300km west of Broome—and was part of a study that has revised what we know about the longevity of tropical fish.

The research identified 11 individual fish that were more than 60 years old, including a 79-year-old red bass also caught at the Rowley Shoals. Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) Fish Biologist Dr Brett Taylor, who led the study, said the midnight snapper beat the previous record holder by two decades. “Until now, the oldest fish that we’ve found in shallow, tropical waters have been around 60 years old,” he said. “We've identified two different species here that are becoming octogenarians, and probably older.”

Dr Taylor said the research will help us understand how fish length and age will be affected by climate change.

“We’re observing fish at different latitudes—with varying water temperatures—to better understand how they might react when temperatures warm everywhere,” he said. The study involved four locations along the WA coast, as well as the protected Chagos Archipelago in the central Indian Ocean. It looked at three species that are not targeted by fishing in WA; the red bass (Lutjanus bohar), midnight snapper (Macolor macularis), and black and white snapper (Macolor niger). Co-author Dr Stephen Newman, from the WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, said long-lived fish were generally considered more vulnerable to fishing pressure.

“Snappers make up a large component of commercial fisheries in tropical Australia and they’re also a key target for recreational fishers,” he said. “So, it’s important that we manage them well, and WA’s fisheries are among the best managed fisheries in the world.” Marine scientists are able to accurately determine the age of a fish by studying their ear bones, or ‘otoliths’. Fish otoliths contain annual growth bands that can be counted in much the same way as tree rings. Dr Taylor said the oldest red bass was born during World War I.

“It survived the Great Depression and World War II,” he said. “It saw the Beatles take over the world, and it was collected in a fisheries survey after Nirvana came and went.” “It’s just incredible for a fish to live on a coral reef for 80 years.”

December 1 2020

The research is published in the journal Coral Reefs.

Funding was provided by the Bertarelli Foundation and contributed to the Bertarelli Programme in Marine Science.

Abundant corals and fishes emerge from the ancient contours of Arafura Marine Park

Scientists have collected the first fine-scale maps and imagery of reefs and submarine canyons in the rarely visited Arafura Marine Park, revealing seafloor environments with surprisingly diverse coral and fish communities. The survey team from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and Geoscience Australia returned to Darwin on the weekend after a two-week voyage on RV Solander. The voyage was supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program Marine Biodiversity Hub.

AIMS Research Program Leader, Dr Karen Miller, said there were vast knowledge gaps in the northern marine bio-region and this new knowledge would enable Australia to better understand and protect the universal value of the environment. “Information from this research voyage will provide critical baseline data to guide the management and protection of the Arafura Marine Park and sea country,” Dr Miller said. “This in turn will contribute to sustainable economic opportunities, and provide for the enjoyment and benefit of this special environment for current and future generations.”

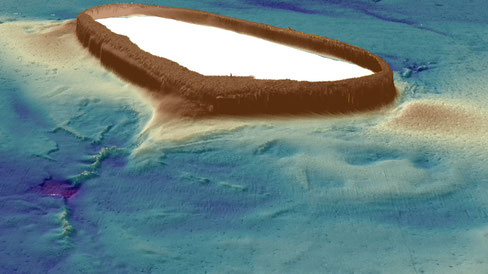

The survey focused on deep and shallow pockets of reef amid the park’s sediment plains. These reefs are where invertebrates such as sponges and corals can attach and form habitat for other marine life. In the north of the park, at the outer edge of Australia’s continental shelf, the scientists visited Pillar Bank, part of an ancient river system that began its transformation to ocean some 14,000 years ago. In the shallow, southern area of the park, they visited Money Shoal, some 200 km north-east of Darwin. Both areas were mapped in detail using multibeam sonar, covering a total area of 350 square kilometres. Guided by the new maps, scientists stationed baited cameras on the seafloor, towed a video camera behind the ship, and sampled the sediments to build inventories of marine life.

The survey focused on deep and shallow pockets of reef amid the park’s sediment plains. These reefs are where invertebrates such as sponges and corals can attach and form habitat for other marine life.

In the north of the park, at the outer edge of Australia’s continental shelf, the scientists visited Pillar Bank, part of an ancient river system that began its transformation to ocean some 14,000 years ago. In the shallow, southern area of the park, they visited Money Shoal, some 200 km north-east of Darwin.

Both areas were mapped in detail using multibeam sonar, covering a total area of 350 square kilometres. Guided by the new maps, scientists stationed baited cameras on the seafloor, towed a video camera behind the ship, and sampled the sediments to build inventories of marine life.

First published at: https://www.aims.gov.au/news-and-media/abundant-corals-and-fishes-emerge-ancient-contours-arafura-marine-park © 1996-2019 Australian Institute of Marine Science

17 November 2020

Biggest fish in the sea are girls

Female whale sharks grow more slowly than males but end up being larger, research suggests.

A decade-long study of the iconic fish has found male whale sharks grow quickly, before plateauing at an average adult length of about eight or nine metres. Female whale sharks grow more slowly but eventually overtake the males, reaching an average adult length of about 14 metres.

Australian Institute of Marine Science fish biologist Dr Mark Meekan, who led the research, said whale sharks have been reported up to 18 metres long. “That’s absolutely huge—about the size of a bendy bus on a city street,” he said. “But even though they’re big, they’re growing very, very slowly. It’s only about 20cm or 30cm a year.” In conducting the research, scientists visited Western Australia’s Ningaloo Reef for 11 seasons between 2009 and 2019. They tracked 54 whale sharks as they grew—a feat made possible by a unique ‘fingerprint’ of spots on each whale shark that can be used to identify individual fish. AIMS marine scientist Dr Brett Taylor said the team recorded more than 1000 whale shark measurements using stereo-video cameras.

“It’s basically two cameras set up on a frame that you push along when you’re underwater,” he said.

“It works the same way our eyes do—so you can calibrate the two video recordings and get a very accurate measurement of the shark.”

AIMS' Dr Mark Meekan measures the length of a whale shark using a stereovideo camera. Photo: Andre Rerekura

The study also included data from whale sharks in aquaria. Dr Meekan said it is the first evidence that males and female whale sharks grow differently. For the females, there are huge advantages to being big, he said.

“Only one pregnant whale shark had ever been found, and she had 300 young inside her,” Dr Meekan said.

“That’s a remarkable number, most sharks would only have somewhere between two and a dozen. “So these giant females are probably getting big because of the need to carry a whole lot of pups.” Whale sharks are Western Australia’s marine emblem, and swimming with the iconic fish at Ningaloo Reef boosts the local economy to the tune of $24 million a year. But they were listed as endangered in 2016. Dr Meekan said the discovery has huge implications for conservation, with whale sharks threatened by targeted fishing and ships strikes.

“If you’re a very slow-growing animal and it takes you 30 years or more to get to maturity, the chances of disaster striking before you get a chance to breed is probably quite high,” he said. “And that’s a real worry for whale sharks.” Dr Meekan said the finding also explains why gatherings of whale sharks in tropical regions are made up almost entirely of young males. “They gather to exploit an abundance of food so they can maintain their fast growth rates,” he said. Dr Taylor said learning that whale sharks plateau in their growth goes against everything scientists previously thought. “This paper has really re-written what we know about whale shark growth,” he said. Dr Meekan and Dr Taylor are based in Perth, Western Australia. The research was published today in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Feature image: Andre Rerekura

16 September 2020

Mystery pufferfish circles discovered in Australia's north-west

Mystery circles providing evidence of a potential new species of pufferfish have been discovered in Australia’s north-west by researchers at The University of Western Australia and Australian Institute of Marine Science.

The research, published in the Journal of Fish Biology, placed the discovery at more than 5500km away from the only other similarly described structures off Amami-Oshima Island in southern Japan. The discovery was made on the North West Shelf of Western Australia when 22 mystery circles were spotted on video footage collected by Fugro during an inspection of the Echo Yodel subsea infrastructure – operated by Woodside on behalf of the North West Shelf Project participants – and while surveying fish along the ancient coastline.

The circles, which are the first to be found in Australia, were recognised by the researchers as the complex underwater structures created by the white-spotted pufferfish previously thought to be found only in southern Japan.

Most notably the size, number of ridges and presence of an intricate central circle with two outer rings makes them comparable to those found in Japanese waters. Originally found at depths of less than 30m in Japan, the finding in the north-west extends their depth occurrence to 137m. Sightings of pufferfish were captured in the immediate vicinity of the circles, near the subsea infrastructure, from Woodside footage using a remotely operated vehicle and an autonomous underwater vehicle, although further investigation was needed to classify the species.

Lead author Todd Bond from UWA’s Oceans Institute and School of Biological Sciences said the discovery of the unique circle structures were most likely produced by a male pufferfish species to use as a nest.

“The pufferfish species responsible cannot be identified from the images collected but it is possibly a new species,” Mr Bond said. “Not only does this discovery spark intrigue and wonder among scientists and the general public, it also provides an insight into the reproductive behaviour and evolution of pufferfish globally.”

Matthew Birt from AIMS said the discovery showed the importance of working alongside industry to uncover the wealth of information so far undiscovered. “Industry routinely conduct video surveys of their assets which are often located in deep and remote waters,” Mr Birt said. “So it’s great that operators of oil and gas infrastructure share their video imagery to build on our existing scientific knowledge. “We can now focus on mapping the distribution of these elaborate pufferfish structures and plan scientific expeditions to collect biological samples so that we can identify and classify the fish.”

First published at https://www.aims.gov.au/news-and-media/mystery-pufferfish-circles-discovered-australias-north-west

17 September 2020

Aerial surveys can keep swimmers and sharks safe

A new study has found that drones have the potential to contribute to effective shark bite management strategies that do not require culling sharks or killing other animals as by-catch. This new study from Southern Cross University looks at “developing the use of drones for non-destructive shark management and beach safety.” The study’s author Dr Andrew Colefax has used drones fitted with artificial intelligence technology to track more than 100 great white sharks along the coast of New South Wales.

In his report, he says there is an increasing need to address human-wildlife conflict in ways that support conservation. However, with current approaches, this balance is seldom achieved. “Shark bites are a well-known human-wildlife conflict, which has presented many management challenges. White (Carcharodon carcarius), bull (Carcharhinus leucas) and tiger (Galeocerdo cuvier) sharks are responsible for the majority of shark bite incidents, both in Australia and globally. Traditionally, addressing perceptions of shark bite risk from these species involved lethal approaches (e.g. mesh nets and drumlines). However, social attitudes are changing towards having greater conservation sentiment, and the cost to wildlife of lethal strategies is increasingly criticised. Therefore, there is widely acknowledged need for a reliable alternative to mitigating shark bites that does not impact marine wildlife. Drones (unmanned aerial vehicles) may contribute to a solution that reduces shark bite risk to a socially acceptable level."

According to the study, overall, drones have potential to contribute to effective shark bite management strategies that do not require culling sharks or impacting bycatch species commonly affected by lethal strategies, and due to the rapidly advancing development of drone-related technologies, the utility of drones for reducing the risk of shark bites can be further improved upon. Read the full study.

It’s vital that we ensure the safety of beachgoers as well as protect sharks and their key role in ocean health.

First published: https://www.seashepherd.org.au/latest-news/drones-sharks-study/

15 September 2020

First ever global survey of reef sharks reveals widespread decline

A landmark new study published today in Nature by Global FinPrint reveals sharks are virtually absent on many of the world’s coral reefs. Sharks were not observed on nearly 20 percent of the 371 reefs surveyed in 58 countries, indicating a widespread decline that has largely gone undocumented until this global survey.

Fortunately, Australia is a country where shark populations on coral reefs are still largely intact. The most common shark species observed were grey reef, whitetip reef and blacktip reef sharks.

Dr Mark Meekan, from the Australian Institute of Marine Science in Perth and Principal Investigator for the Global FinPrint project in the Indian Ocean region said good management plays a key role in determining the status of reef sharks. “Our survey not only reveals the plight of sharks on coral reefs, which is in many cases very worrying, it also reveals how control of shark fishing can make effective conservation gains,” Dr Meekan said. Australia was one of several nations where the study revealed that shark conservation on coral reefs is working. Other nations include the Bahamas, the Federated States of Micronesia, French Polynesia, the Maldives, and the United States. Dr Meekan said reef sharks play an important role maintaining a healthy ecosystem. “Sharks are important for the ecology of coral reefs, particularly at a time when they are facing so many other threats from climate change. But few people realise that reef sharks are also an important part of the economies of many small island nations around the world because they are a key attraction for reef tourism. “Rebuilding shark numbers isn’t just good sense ecologically – it also makes good sense economically,” Dr Meekan said.

AIMS scientist Dr Michelle Heupel, and Global FinPrint Principal Investigator in the Western Pacific, said this world first study relied on cooperation and collaboration of colleagues in many nations and territories across the globe. “Hundreds of scientists, researchers, and conservationists captured and analysed more than 15,000 hours of video from surveys of 371 reefs in 58 countries, states and territories around the world over four years. “We hope these findings will help countries continue to maintain shark populations or make management changes to improve their status,” she said. Funded by the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, the Global FinPrint’s survey data were generated from baited remote underwater video systems (BRUVS) consisting of an underwater video camera attached to a bait bag containing a small amount of fish. Coral reef ecosystems were surveyed with BRUVS in four key geographic regions: The Indo-Pacific, Pacific, the Western Atlantic and the Western Indian Ocean. As well as AIMS, other coordinating organisations working on the project came from Florida International University, Curtin University, Dalhousie University, and James Cook University.

For more information and a new global interactive data-visualized map of the Global FinPrint survey results, visit https://globalfinprint.org.

First published at: https://www.aims.gov.au/news-and-media/first-ever-global-survey-reef-sharks-reveals-widespread-decline

23 July 2020

Coral bleaching detected off Kimberley coast

Scientists have discovered a significant coral bleaching event at one of Western Australia’s healthiest coral reefs.

More than 250 kilometres west of Broome, the Rowley Shoals is one of only two reef systems in the State to have recorded high and stable coral cover throughout the past decade.

In April and May 2020, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) conducted surveys of the reef system, supported by Parks Australia and Australian Border Force, to confirm reports of significant coral bleaching.

Data obtained revealed that bleaching was variable across the Rowley Shoals, with estimates ranging between one and 30 percent of the corals bleached. One site on Clerke Reef experienced up to 60 percent of the corals bleached. Further aerial surveys of the North Kimberley and Lalang-garram marine parks found coral bleaching to be patchy and less severe than at Rowley Shoals.

Following temperature alerts issued by the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM), aerial flights by Australian Border Force provided the first evidence of coral bleaching at Western Australia’s remote coral reef atolls Image: Australian Border Force DBCA’s Marine Monitoring Coordinator Dr Thomas Holmes attributed the bleaching to an unusually warm and prolonged ocean temperature off the coast of the Kimberley. “By global standards, Western Australia still has relatively healthy reefs, but seawater temperature is increasing around the world as a result of climate change. This is causing corals to bleach and die from heat stress more frequently and at scales not previously observed,” Dr Holmes said.

The extent and severity of bleaching varied across the Rowley Shoals, ranging from 10% to over 60% bleaching at some sites. Image: Chris Tucker

AIMS’ coral ecologist Dr James Gilmour said that bleaching had badly affected other offshore atolls and the inshore Kimberley region in 2016/17. “Coral bleaching can devastate entire reef systems and dramatically alter associated communities of marine plants and animals,” Dr Gilmour said. “Some corals will regain their symbiotic algae and recover, while those corals that have been severely bleached are likely to die.”

At the worst affected sites, even the robust massive corals at 20m depth had bleached. Image: Chris Tucker

Follow up surveys as a part of DBCA and AIMS long-term monitoring programs are currently planned for later this year to determine the full effect of the event on the coral communities. The bleaching survey of Rowley Shoals was conducted as part of AIMS’ North West Shoals to Shore Research Program funded by Santos Ltd.

First published https://www.aims.gov.au/news-and-media/coral-bleaching-detected-kimberley-coast

14 July 2020

Coastal pollution reduces genetic diversity of corals, reef resilience

A new study published in the journal PeerJ by researchers at the University of Hawaii found that human-induced environmental stressors have a large effect on the genetic composition of coral reef populations in Hawaii.

The National Science Foundation-funded scientists confirmed that there is an ongoing loss of sensitive genotypes in nearshore coral populations due to stressors from poor land-use practices and coastal pollution. This reduced genetic diversity compromises reef resilience.

This research provides valuable information to coral reef managers in Hawaii and around the world who are developing approaches and implementation plans to enhance coral reef resilience and recovery through reef restoration and stressor reduction.

The study identified that genetic relationships between nearshore corals in Maunalua Bay, Oahu, and those from sites on West Mau were closer than relationships to corals from the same islands, but farther offshore.

This pattern can be described as isolation by environment in contrast to isolation by distance. This is an adaptive response by the corals to watershed discharges that contain sediment and pollutants from land.

“While the results were not surprising, they demonstrate the need to control local sources of stress while addressing the root causes of global climate change,” said Robert Richmond, director of the Kewalo Marine Laboratory and co-author of the study. “The findings show the need to track biodiversity at multiple levels.”

While the loss of coral colonies and species is easy to see with the naked eye, molecular tools are needed to uncover the effects of stressors on the genetic diversity within coral reef populations. “This study shows the value of applying molecular tools to ecological studies supporting coral reef management,” stated Kaho Tisthammer, lead researcher on the paper.

The work was a collaborative effort among researchers at the university’s Kewalo Marine Laboratory, Pacific Biosciences Research Center, and the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology. “This work highlights the importance of limiting pollution, sediment, and agricultural runoff to nearshore coral reefs,” says Dan Thornhill, a program director in NSF’s Division of Ocean Sciences. “Protecting biodiversity is essential, as that diversity is needed in helping corals and other marine life adapt to changing oceans. Selecting for resilience to pollution may eliminate coral genotypes that resist disease, tolerate higher temperatures, and continue to grow in more acidic and oxygen-depleted waters.”

9 April 2020

First published: https://www.miragenews.com/coastal-pollution-reduces-genetic-diversity-of-corals-reef-resilience/

Coronavirus is killing Australia's lobster export market

Currents are strong around the Torres Strait Islands, lying between Australia’s northern-most tip and Papua New Guinea. When the tidal conditions are right and the waters relatively still, though, up to 230 islanders – a sizeable percentage of the islands’ roughly 4,000 indigenous inhabitants – will board small boats and head out to the surrounding reefs. There they will dive down and search the underwater outcrops for lobsters, grabbing the crustaceans by hand. It’s laborious work compared with lobster fishing in other parts of Australia, where fishers bait “pots”, then simply pull up the pots with lobsters inside. The tropical rock lobsters of the Torres Strait, however, are sensitive creatures and generally won’t crawl into a trap. By hand is the only sure way to catch them. But, until a few weeks ago, it has been worth it. A fisher can sell a live lobster from these waters for $65-95 a kilogram. That makes it worth holding them in water-filled crates and then flying them to wholesalers in Cairns. There they are processed and transported to domestic and international markets.

The most lucrative market is China. Its appetite for live rock lobster makes up about half the value of Australia’s seafood exports (A$660 million of A$1.4 billion). Now, though, lobster fishers are staying home. There hasn’t been a regular lobster shipment to China since January 26. With the Wuhan coronavirus suspected to have originated from wild animals in the city’s Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, Chinese authorities have temporarily banned all wild animal trade. Lobster and other wild-caught aquatic products are exempt from the ban, but demand has plummeted due to people staying home and avoiding both markets and restaurants.This collapse has come at a time that would normally be one of peak demand, and peak prices, due to Chinese New Year festivities. Our industry sources report prices for live lobsters are down 50% to 80%.

It’s a huge blow to the economy of Torres Strait, along with the rest of Australia’s live seafood export industry.

Loss of livelihoods

Lobster fishing is among the highest-value economic activities in the strait. Indigenous islanders have limited alternatives to make money, given their geographical isolation. As scientists fortunate to work closely with traditional owners in the Torres Strait over the past decade, we’re saddened to see this devastating impact on livelihoods.

CSIRO researchers have worked in the strait for more than three decades to help local people sustain their traditional way of life and conserve the marine environment for future generations. This is no easy feat, considering the resources are also shared with an Australian non-Islander sector and traditional owners from Papua New Guinea. The region’s wild marine fisheries have been thriving thanks to good management and a strong sense of custodianship by the Islanders.

New harvest strategies for fishing lobster and bêche-de-mer (sea cucumbers) were implemented in December 2019. These took years of research and consultation. This included augmenting scientific surveys with information from fishers to work out sustainable catches. The new strategies followed a disastrous lobster-fishing year in 2018, when our scientific surveys suggested the lobster population was in trouble due to conditions created by extreme El Niño events. The fishery had to be closed two months early, with substantial economic impact. It was nonetheless an example of Torres Strait Islanders putting sustainability before short-term gain.

No offsets

Now they have the coronavirus to contend with. The loss of income from those in the fishing business affects other small businesses and ripples throughout the local community. Selling to the frozen seafood market is an option, but prices are much lower, and there’s a point at which the time, effort and cost of catching a tropical rock lobster make it uneconomical. Boat fuel, for one thing, is expensive. Sales of frozen seafood to China have also taken a dive. For some Australian fisheries it’s possible taking fewer fish this season will mean a larger fish population next year. So next year’s catch quotas could be adjusted up without jeopardising the marine population. This could partially offset losses this year. But that’s not an option for the Torres Strait lobster fishery. That’s because by the time a lobster is big enough to catch, usually in its third year of life, it is also ready to migrate, walking several hundred kilometres to the east of the fishery area. So catching fewer lobsters this year won’t mean they are around to catch next year. It is a unique fishery in this regard.

Planning sustainable exports

This impact of the coronavirus on Torres Strait Islanders shows how connected global trade now is. What it also demonstrates is the importance of deliberate and distributed growth in export

markets for them to be sustainable. Heavy dependence on a single market carries a big risk. As things stand, we can expect demand for seafood in China will remain low for some time to come. This

is an opportune time to rethink sustainable export growth strategies.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

19 February 2020

Marine Science Australia

Marine Science Australia